By Katlyn Stoneburner – Features Editor

When we think of winter, images of snow-covered landscapes and majestic reindeer often come to mind, evoking a sense of seasonal wonder. Yet, in Quebec’s wilderness, the plight of their close relatives—the caribou—tells a much graver story. Once thriving symbols of the province’s natural heritage, the Val-d’Or, Charlevoix, and Pipmuacan caribou herds are now teetering on the brink of collapse. Conservationists and researchers are grappling with the daunting challenge of reversing decades of decline, fighting to ensure these iconic animals remain a part of Quebec’s winter landscape for generations to come.

These animals, once thriving in the old-growth forests of the boreal region, are now struggling to survive as their populations dwindle. The plight of Quebec’s woodland caribou is emblematic of the delicate balance between environmental stewardship and economic development. The decline has been attributed to a combination of habitat loss, predation, and the impacts of climate change. Industrial activities such as logging and mining have fragmented the forests they rely on for shelter and food, leaving them vulnerable to predators and environmental shifts.

For Leea Rebeca Ruta, a recent Bishop’s University graduate and current master’s student at the Université de Sherbrooke, the issue is deeply personal and intellectual. Her humanities education, she argues, offers a unique perspective on this ecological crisis.

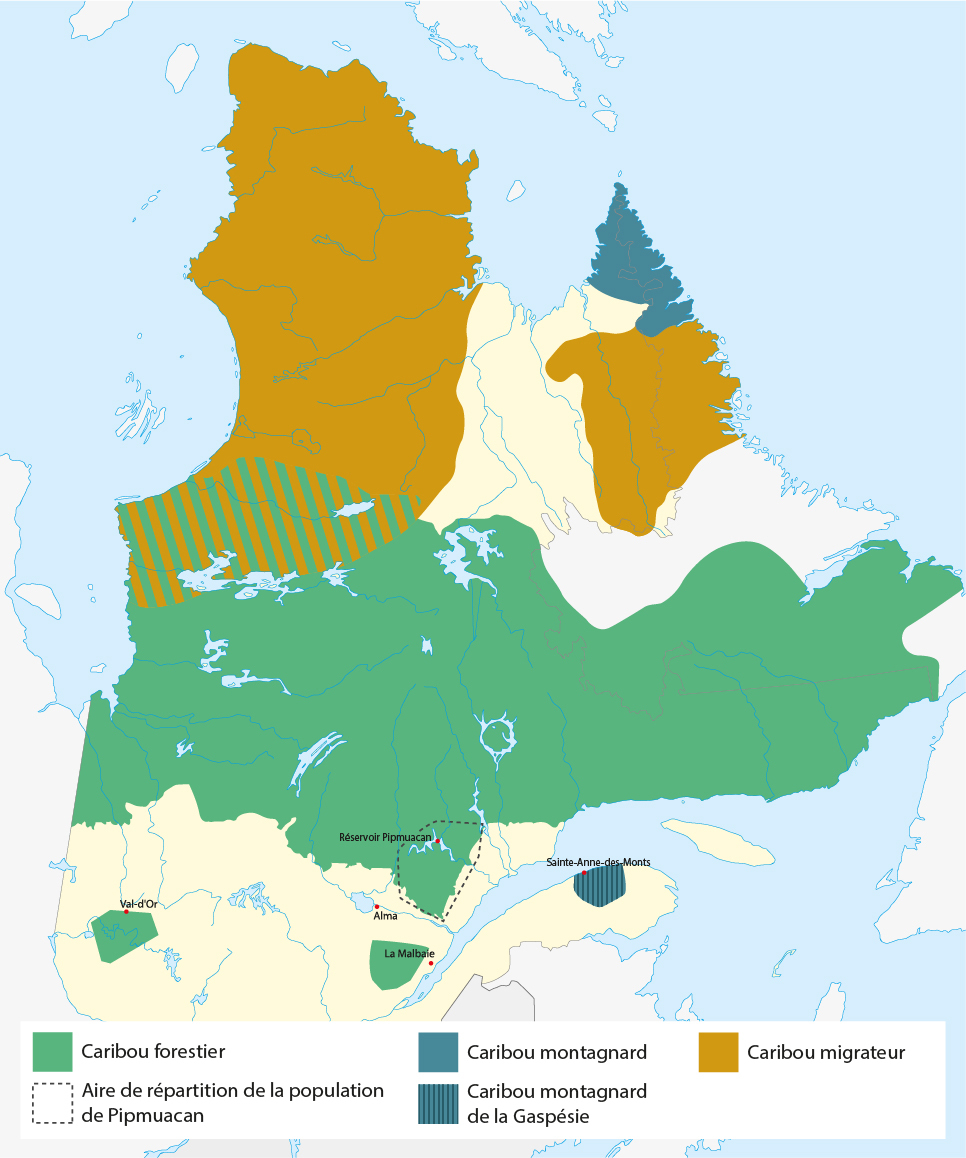

Caribou are divided into three ecotypes in Quebec: migratory, mountain, and woodland. The woodland caribou are particularly at risk, with only an estimated 7,000 to 8,000 individuals remaining. In regions like Val-d’Or and Charlevoix, populations are so vulnerable that enclosures are used to protect them. Yet the decline persists.

Map produced by Nature Québec with data from the Government of Quebec

Despite their protected status under federal and provincial law since the early 2000s, conservation efforts have lagged. The federal government recently issued an emergency decree to protect the species, a move that has sparked controversy. Quebec’s forestry cooperatives have pushed back, submitting formal objections and raising questions about jurisdictional authority. Natural resources, they argue, fall under provincial governance. “It’s a constitutional gray area,” Ruta explains, noting the tension between federal mandates and provincial autonomy.

However, for Ruta, the caribou’s plight transcends political and economic debates. She believes it highlights the need for a more holistic view, one informed by humanities disciplines like philosophy and ethics. “Everyone else in my class comes from biology or engineering. They focus on the science or the economics of the issue. But my background helps me see this as a social issue too,” she says. Her education has shaped her understanding of the caribou not just as a species but as a symbol of humanity’s relationship with nature.

This perspective is essential in a conversation often dominated by numbers and policies. Old-growth forests, home to caribou, are critical for biodiversity, carbon sequestration, and cultural significance, particularly for Indigenous communities. Quebec’s Superior Court has even ruled that the province failed to adequately consult First Nations in managing caribou populations. “The cultural and spiritual importance of these animals is rarely discussed,” Ruta says, underscoring the importance of Indigenous voices in environmental decision-making.

The symbolism of the caribou goes beyond ecological importance—it’s a reminder of moral responsibility. “We’re literally deciding the existence of another living being,” Ruta reflects. “It’s not just about jobs or economics; it’s about what kind of world we want to leave for future generations.” This sentiment resonates with broader themes of stewardship and sustainability. Just as educators think about how their work impacts upcoming generations, environmental policymakers must consider the long-term consequences of their actions.

For students at Bishop’s, this issue is a call to awareness. While the school’s secluded location in the Eastern Townships fosters a close-knit community, it can also create a sense of disconnection from larger provincial issues. “Bishop’s is in a microclimate, both geographically and socially,” Ruta notes. She hopes her work and discussions on the caribou crisis will inspire her peers to look beyond their immediate surroundings and consider the broader implications of environmental challenges.

Ultimately, the caribou’s fate serves as a metaphor for the challenges of living sustainably in a rapidly changing world. Whether it’s a debate about forestry practices or global warming, the questions remain the same: What is our moral obligation to other species? How do we balance present needs with future sustainability? And, most critically, how can we approach these issues with empathy and ethical responsibility?

For Ruta, her humanities education has provided the tools to grapple with these questions, offering a lens that prioritizes both the practical and the philosophical. “I feel like I’m a better human because of it,” she says. It’s a sentiment that echoes the caribou’s silent plea: to be seen not just as numbers or resources but as an integral part of a shared ecosystem.