By Virginia Rufina Marquez-Pacheco – Contributor

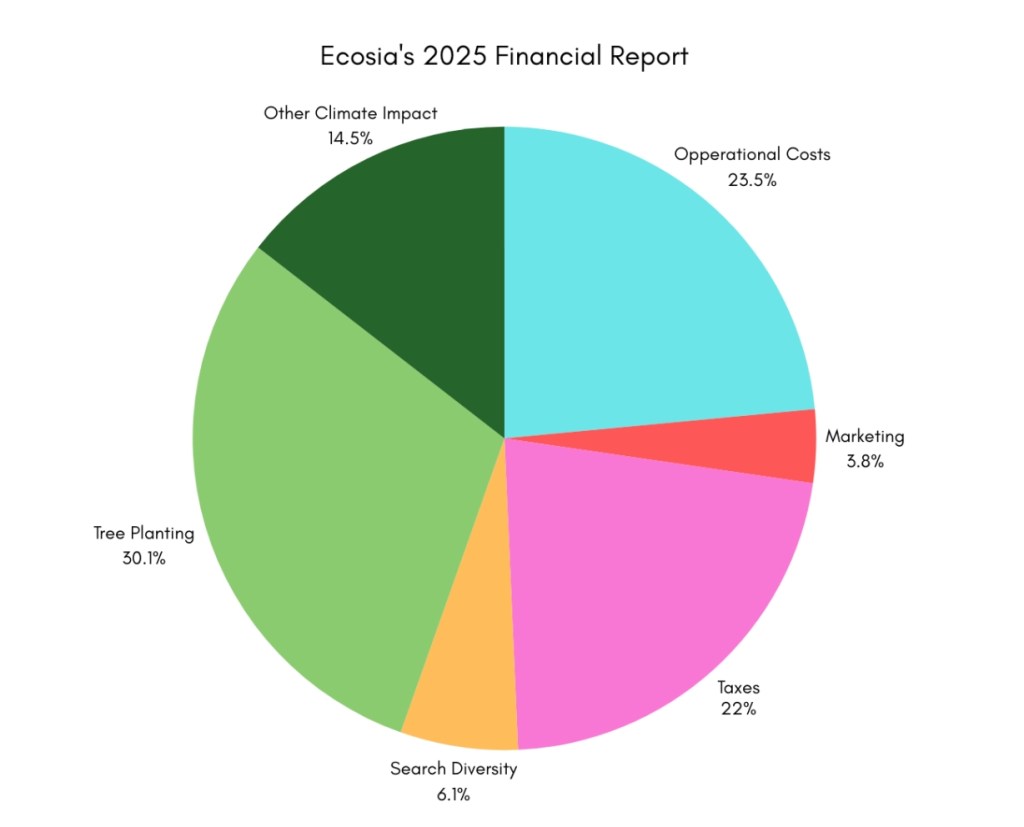

Graphic courtesy of Damita Melchi

The genocide in Palestine has brought to light not only issues of human rights and indigeneity, but it has also put the spotlight on the meaning of neutrality. Across the world, as students mobilized to push their university institutions and student associations to take a clear stance against the genocide, they have often been met with the response that universities are apolitical environments. This statement is not only misleading, but it can also result in perpetuating harm.

To begin, it is important to define what I mean by an institution being “political.” Politics are usually associated with the actions of politicians and governments. This narrow view of what counts as political institutions (i.e. government bodies) ignores the impact that institutions traditionally considered non-political can have on the public and personal lives of people. After all, what is politics; but the governance and guidance of relationships between people and between resources within societies. In feminist and student activist circles, this idea can be summed up in the phrase “the personal is political.” When it comes to universities, one can easily see how their actions and decisions can have a lasting impact on societal relationships.

A direct way in which universities are actively political institutions is by their direct participation in governance. After all, universities, like other institutions, actively engage with the government on a local and national level for a variety of reasons. For example, last year, English universities across Québec engaged in extensive negotiations with the provincial government to avert the latter’s proposed tuition hikes. Moreover, universities are compelled to continually adapt to and influence provincial and federal law. Such is the case with the recent changes to sexual violence prevention and response policies and laws, an area where universities publicly declare their intentions to change the culture.

From a civic perspective, universities are also key players. Civic participation is undeniably a form of politics, and universities have historically been a scene for these activities. From student movements to the formation of budding politicians, universities shape the way social issues are addressed. For example, the anti-apartheid student movement forced many university institutions to divest from companies supporting and enabling apartheid in South Africa. The decision made by the university administration to divest sent a strong political message that undoubtedly contributed to the end of the apartheid regime.

Universities are also political players on an academic level. From a practical standpoint, the decision on who and what to teach impacts the social and therefore political fabric of our societies. The education students receive undoubtedly impacts the political views that they will act upon as engaged citizens, especially should they choose to follow a career in politics. There is no denying that the decision to teach about the negative impacts of systemic racism, for example, leads to negative perceptions of this problem. If this were not the case, there would not be such an intense battle in the United States about the teaching of African American and queer studies. What universities teach matters.

Lastly, there is extensive precedence on the participation of universities in global issues, even when that participation boils down to so-called neutrality. For example, when Russia first invaded Ukraine, Bishop’s University chose to take a public stance on the issue, even choosing to raise the Ukrainian flag on campus. Even the choice of staying silent in the face of issues of violence and oppression is a political stance. An example of this silence was the historical “neutrality” or inaction by university institutions in the face of systemic sexual violence. The lack of action to tackle this issue seemed to imply approval for that culture and allowed it to perpetuate. Neutrality is a political stance, and when harm is being perpetuated, “neutrality” permits the perpetuation of harm. As Desmond Tutu said, “If you are neutral in situations of injustice, you have chosen the side of the oppressor. If an elephant has its foot on the tail of a mouse and you say that you are neutral, the mouse will not appreciate your neutrality.”

Thus, it is clear that universities are not and have never been apolitical nor neutral institutions. Their choices and their voices matter, even the choice to do or say nothing. To deny the political nature of universities is to make room for the perpetuation of harmful behaviors should they choose to allow it by either encouraging it or by doing nothing to stop it.