By Sufia Langevin – Associate Editor & Colin Ahern – Opinions Editor

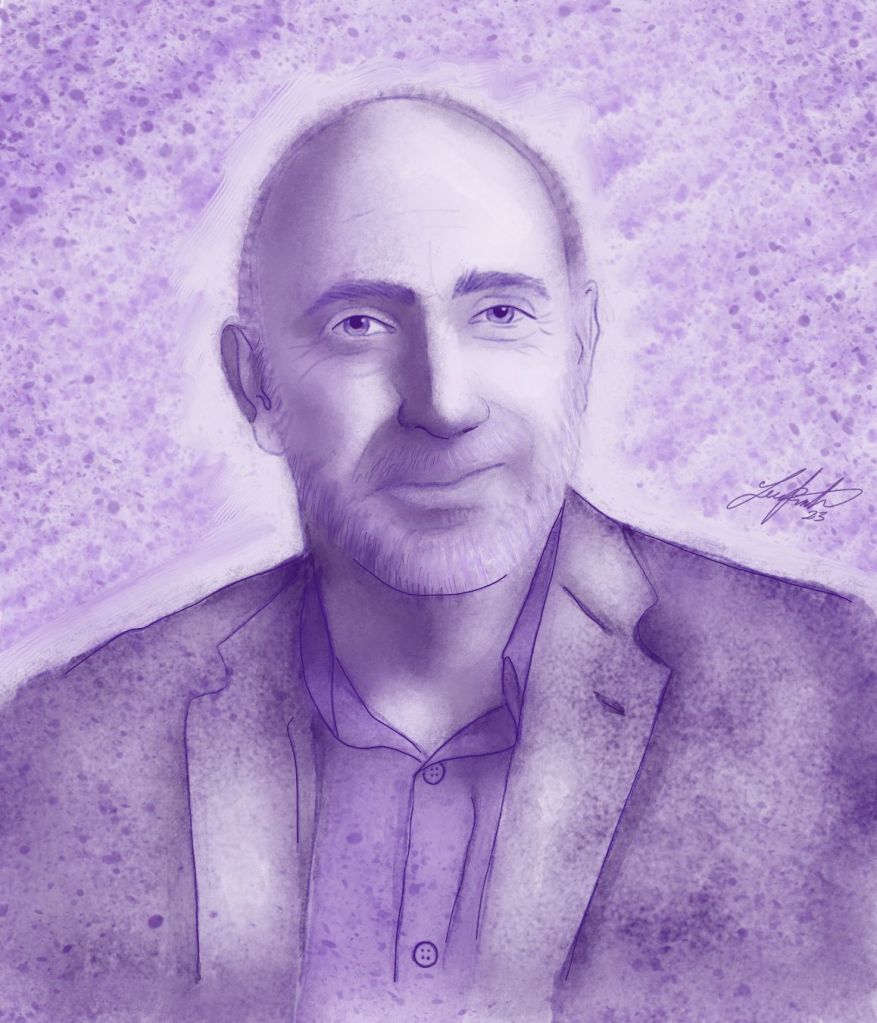

On Feb. 21, Jared Fishman, a civil rights lawyer and social justice innovator, gave a Donald Lecture in Centennial Theatre on the United States justice system. Jared drew on his fourteen years of experience as a federal prosecutor to discuss his perspective on the ways in which justice is served within the court system and explained his research and innovation’s role in creating a more equitable justice system.

Fishman started by asking the key question “what is justice?” and focused the beginning of the lecture on the punitive nature of the justice system in the status quo.

He brought up an example of how the success of a prosecutor is measured in the number of years for which they were able to put criminals away. This meant that rather than delivering punishments proportional to crimes, the justice system sought to deliver the greatest possible punishment for the crimes committed.

This directly opposes the principle of restorative justice, which seeks to remedy the harms created and prioritize the needs of the victim. This distinction is critical since many victims have been harshly sentenced due to the focus on punishment, rather than healing. Fishman focused on the desire to prevent crime in the future by addressing the root cause, rather than punishing the occurrence. When showing statistics, Fishman revealed that offenders who received harsh sentences were substantially more likely to break the law again than those who served forgiving sentences or alternatives to prison. This furthers the notion that the justice system operates with the intent of punishment by largely producing punitive results.

The premise of restorative justice and equity are crucial when analyzing the disproportionate number of incarcerations and punishments against African-Americans. Fishman unmasked how police officers in the U.S. arrested a far greater number of Black people, despite the fact that the majority of these arrests never made it to court due to issues such as lack of evidence.

Fishman’s concern was not focused on the quantity of convicted arrests but the number of people who were not convicted. He found that it took three months longer for African-Americans to be released for issues such as inconclusive evidence, compared to their White counterparts. Being in the court system is enormously expensive and the toll of three months can be financially devastating. Beyond hearing costs, people who were arrested frequently lost their jobs due to their arrest. This results in a cycle of economic damage to African-American communities, creating higher poverty rates, often connected with higher crime rates. Members of the Bishop’s community were particularly engaged during the question period, discussing their ideas of justice and relating the thesis to the RCMP’s treatment of Indigenous peoples in Canada.

Fishman’s lecture focused largely on how the systems intended to deliver justice were contributing to injustice. He explained that every system produces the results it was designed to produce, exposing the underlying systemic racism that pervades the United States justice system. Discussing this truth in our community is the first step to a more equitable society.

For more information you can visit Fishman’s Justice Innovation Lab Instagram page @lab4justice.